Fastest Convolution Kernel on LeetGPU

Optimizing CUDA code to perform Convolution with 3D kernels from scratch

In this article, I present a CUDA kernel implementation for computing the Convolution Operation operation. This mathematically performs 3D cross-correlation using a 3D kernel.

Mathematically, we have a 3D kernel (which is a weight matrix) with which we compute our output matrix as follows:

This is more precisely known as a cross-correlation operation (convolution actually has kernel mirrored/flipped). In this case, we actually shrink our output dimensions as well. (We are not applying padding here.)

This happens because you can imagine an output coordinate at the boundary. Suppose we have input shape D x R x C where D is depth, R is rows and C is columns. Then, a coordinate at (D-1, R-1, C-1) will, by that formula, need input at (D, R, C) if the kernel is of shape 2x2x2, but that input doesn't exist. To remedy this, people apply padding, symmetrically, which could be in the form of adding zeros, adding the image mean/median value, mirroring the image, copying over the boundary value, etc. But this also slightly changes our cross-correlation formula above. Here, represent the padding applied along each dimension.

But, we're not really applying padding here. You could say, I was padding out this section 😉.

But really, I think it's useful to understand the boundary checks and other indexing choices below 🙂 Without padding, we therefore reduce our dimensions to , , respectively.

Understanding the Algorithm

A naive solution just assigns 1 thread to do one output computation. I.e., each thread just goes and computes a single output value

#define TILE 8 __global__ void conv3d(const float* input, const float* kernel, float* output, int input_depth, int input_rows, int input_cols, int kernel_depth, int kernel_rows, int kernel_cols){ // 8x8x8 blocks are created int depth = threadIdx.z + blockDim.z * blockIdx.z; int row = threadIdx.y + blockDim.y * blockIdx.y; int col = threadIdx.x + blockDim.x * blockIdx.x; // output dimensions are computed int out_rows = input_rows - kernel_rows + 1; int out_cols = input_cols - kernel_cols + 1; int out_depth = input_depth - kernel_depth + 1; // Only apply kernel if within bounds if(row < out_rows && col < out_cols && depth < out_depth){ float v = 0; // kernel is simply a triple for loop for(int dz = 0; dz < kernel_depth; dz++){ // some caching for reducing computation const int in_d = (depth + dz) * input_rows * input_cols; for(int dy = 0; dy < kernel_rows; dy++){ const int in_base = in_d + (row + dy) * input_cols + col; const int k_base = (dz * kernel_rows + dy) * kernel_cols; for(int dx = 0; dx < kernel_cols; dx++){ v += input[in_base + dx] * kernel[k_base + dx]; } } } output[depth * out_cols * out_rows + row * out_cols + col] = v; } }

In short the kernel above, literally just applies the formula once for each thread. This takes

about 4ms to run. We start by marking out thread indices as always. Then we just iterate

over the kernel, and accumulate into . But at this point, the kernel depends on global memory

accesses too much! In the previous article, we learnt that each global reads are very slow, and can take 100s of core clock cycles. This kernel makes too many global memory accesses (basically, every calculation). For every multiplication and add, we're loading one memory address!

Collaboration and Coalescing

The main observation is that adjacent output addresses share a lot of input addresses. Just look at computing a 5x5x5 kernel and output indices (0, 0, 0) and (0, 0, 1). All input addresses from (0, 0, 1) to (4, 4, 4) are used by both of these! So, the natural next step is to use shared memory and load these values collaboratively. Each read instead takes 10s of cycles rather than 100s from shared memory.The important thing to note however is, we want to actually load in a wider amount. For example, if our output tile / block is 8x8x8, then, we want to load (8 + kernel - 1) x (8 + kernel - 1) x (8 + kernel - 1) because the elements towards the borders (for example (7, 7, 7)) actually need to read in more input elements (example: (8, 8, 8)) so if we just loaded 8x8x8 elements from input to our shared memory, we'd be only able to write out (8 - kernel + 1)^3 output values - much less! That's why the collaborative load is actually a nested for-loop.

// Pre-cache the kernel for more efficiency __constant__ float shared_kernel[125]; #define TILE 8 #define SIZE (TILE) #define MAX_K 5 __global__ void conv3d(const float* input, float* output, int input_depth, int input_rows, int input_cols, int kernel_depth, int kernel_rows, int kernel_cols){ int tidy = threadIdx.y; int tidx = threadIdx.x; int tidz = threadIdx.z; int row = tidy + SIZE * blockIdx.y; int col = tidx + SIZE * blockIdx.x; int depth = tidz + SIZE * blockIdx.z; // Shared memory loads in a larger amount __shared__ float Ms[SIZE + MAX_K][SIZE + MAX_K][SIZE + MAX_K]; // Load values in collaboratively for(int dz = tidz; dz < SIZE + kernel_depth; dz += TILE){ // Increment by SIZE for coalesced memory loads int inp_z = SIZE * blockIdx.z + dz; for(int dy = tidy; dy < SIZE + kernel_rows; dy += TILE){ // Increment by SIZE for coalesced memory loads int inp_y = SIZE * blockIdx.y + dy; for(int dx = tidx; dx < SIZE + kernel_cols; dx += TILE){ // Increment by SIZE for coalesced memory loads int inp_x = SIZE * blockIdx.x + dx; Ms[dz][dy][dx] = (inp_z < input_depth && inp_y < input_rows && inp_x < input_cols) ? input[(inp_z * input_rows + inp_y) * input_cols + inp_x] : 0.0f; // identity value = 0 } } } // Wait till all threads have loaded their values in __syncthreads(); const int out_depth = input_depth - kernel_depth + 1; const int out_rows = input_rows - kernel_rows + 1; const int out_cols = input_cols - kernel_cols + 1; // Just compute! if(row < out_rows && col < out_cols && depth < out_depth){ float v = 0; #pragma unroll for(int dz = 0; dz < kernel_depth; dz++){ const int z_pos = tidz + dz; const int k_base_z = dz * (kernel_rows * kernel_cols); #pragma unroll for(int dy = 0; dy < kernel_rows; dy++){ const int y_pos = tidy + dy; const int k_base = k_base_z + dy * kernel_cols; #pragma unroll for(int dx = 0; dx < kernel_cols; dx++){ const int x_pos = tidx + dx; // Use shared memory not input! v += Ms[z_pos][y_pos][x_pos] * shared_kernel[k_base + dx]; } } } // Write out output[(depth * out_rows + row) * out_cols + col] = v; } }

This kernel is already twice as fast as the first one!

Control Divergence and Coarsening

A keen observer would notice that in the collaborative load step, we make exactly 8 iterations in total (since MAX_K = 5). But whenever we're on the 2nd step, only half the threads will load values in, while the other half do nothing. This is called control divergence, and this is a big inefficiency here, since only 1 out of the 8 steps will NOT exhibit this divergence!So, we implement thread coarsening - each thread is assigned more values that it is responsible for. This reduces some parallelism and makes each individual thread more serial, but it helps reduce the total number of blocks and can actually increase parallelism in that sense. We just introduce a CFACTOR variable which explains how coarsened the thread is. So, CFACTOR of 4 means a thread manages a 4x4x4 sub-grid instead of just 1x1x1 (CUTLASS folks call this value layout). This becomes signficantly more complex to code.

// Pre-cache the kernel for more efficiency __constant__ float shared_kernel[125]; #define TILE 8 #define CFACTOR 2 #define SIZE (TILE * CFACTOR) #define MAX_K 5 __global__ void conv3d(const float* input, const float* kernel, float* output, int input_depth, int input_rows, int input_cols, int kernel_depth, int kernel_rows, int kernel_cols){ int tidy = threadIdx.y; int tidx = threadIdx.x; int tidz = threadIdx.z; // now one block manages SIZE^3 elements not TILE^3 elements int row = tidy + SIZE * blockIdx.y; int col = tidx + SIZE * blockIdx.x; int depth = tidz + SIZE * blockIdx.z; __shared__ float Ms[SIZE + MAX_K][SIZE + MAX_K][SIZE + MAX_K]; // synced load for(int dz = tidz; dz < SIZE + kernel_depth; dz += TILE){ int inp_z = SIZE * blockIdx.z + dz; for(int dy = tidy; dy < SIZE + kernel_rows; dy += TILE){ int inp_y = SIZE * blockIdx.y + dy; for(int dx = tidx; dx < SIZE + kernel_cols; dx += TILE){ int inp_x = SIZE * blockIdx.x + dx; Ms[dz][dy][dx] = (inp_z < input_depth && inp_y < input_rows && inp_x < input_cols) ? input[(inp_z * input_rows + inp_y) * input_cols + inp_x] : 0.0f; } } } __syncthreads(); const int out_depth = input_depth - kernel_depth + 1; const int out_rows = input_rows - kernel_rows + 1; const int out_cols = input_cols - kernel_cols + 1; // Extra outer loops to control coarsning! for(int k = 0; k < CFACTOR; k++){ tidy = threadIdx.y; row = tidy + SIZE * blockIdx.y; for(int i = 0; i < CFACTOR; i++){ tidx = threadIdx.x; col = tidx + SIZE * blockIdx.x; for(int j = 0; j < CFACTOR; j++){ // Regular computation step if(row < out_rows && col < out_cols && depth < out_depth){ float v = 0; #pragma unroll for(int dz = 0; dz < kernel_depth; dz++){ const int z_pos = tidz + dz; int k_base_z = dz * kernel_cols * kernel_rows; #pragma unroll for(int dy = 0; dy < kernel_rows; dy++){ const int y_pos = tidy + dy; const int k_base = k_base_z + dy * kernel_cols; #pragma unroll for(int dx = 0; dx < kernel_cols; dx++){ const int x_pos = tidx + dx; v += Ms[z_pos][y_pos][x_pos] * shared_kernel[k_base + dx]; } } } output[(depth * out_rows + row) * out_cols + col] = v; } // We increase by TILE not by 1 // So, we see that the 8 adjacent threads per column always write to // adjacent memory locations as a result - and it stays coalesced. tidx += TILE; col += TILE; } // This is not motivated by adjacency, rather it's just to have // the same logic and apply it easily row += TILE; tidy += TILE; } depth += TILE; tidz += TILE; } }

In this case, the coarsened kernel is actually the same speed as the regular kernel.

Likely the impact due to serialization is about the same as the impact of control divergence.

Warp Awareness and Smarter Coarsening - the fastest

A warp is a group of threads that execute the exact same instruction (in case of divergence threads are just simply masked).To really be the fastest, we need to realize that warps are actually 32 threads not 8. So, when we placed 8 threads in a row in an 8x8x8 shape, this is inefficient. Each warp is basically split into 4 parts now, spread across rows. Hence, within the warp, the reads are actually not all coalesced.

To make it coalesced, we need to now place 32 threads in a row, i.e., our block should look like: Depth x Rows x 32 (or x64, but 64 is just a bit too big).

But what do we set for Depth and Rows? It's totally unclear at first! If you want to load things shared, then you end up loading (Depth + kernel) x (Rows + kernel) x (32 + kernel). I.e., if you were to leave the Depth or Rows relatively thin (like just 1 or 2), it is really wasteful, since you could have been sharing a lot more across those dimensions.

So, we can do the following. Let's make Rows = 16, and Depth = 1. But instead, we coarsen across Depth to increase sharing memory accesses in that dimension. Our block size is now 16 x 32 = 512 - not too big either.

// Pre-cache the kernel for more efficiency __constant__ float shared_kernel[125]; #define TILE_X 32 #define TILE_Y 16 #define SIZE_X (TILE_X) #define SIZE_Y (TILE_Y) #define MAX_K 5 #define CFACTOR_Z 4 __global__ void conv3d(const float* input, float* output, int input_depth, int input_rows, int input_cols, int kernel_depth, int kernel_rows, int kernel_cols){ int tidy = threadIdx.y; int tidx = threadIdx.x; int row = tidy + SIZE_Y * blockIdx.y; int col = tidx + SIZE_X * blockIdx.x; int depth = CFACTOR_Z * blockIdx.z; // base depth __shared__ float Ms[CFACTOR_Z + MAX_K][SIZE_Y + MAX_K][SIZE_X + MAX_K]; // Reads coarsened across z-axis for(int dz = 0; dz < CFACTOR_Z + kernel_depth - 1; dz++){ int inp_z = depth + dz; for(int dy = tidy; dy < SIZE_Y + kernel_rows; dy += TILE_Y){ int inp_y = SIZE_Y * blockIdx.y + dy; for(int dx = tidx; dx < SIZE_X + kernel_cols; dx += TILE_X){ int inp_x = SIZE_X * blockIdx.x + dx; Ms[dz][dy][dx] = (inp_z < input_depth && inp_y < input_rows && inp_x < input_cols) ? input[(inp_z * input_rows + inp_y) * input_cols + inp_x] : 0.0f; } } } __syncthreads(); const int out_depth = input_depth - kernel_depth + 1; const int out_rows = input_rows - kernel_rows + 1; const int out_cols = input_cols - kernel_cols + 1; for(int k = 0; k < CFACTOR_Z; k++){ // Writes also coarsened across z-axis if(row < out_rows && col < out_cols && depth + k < out_depth){ float v = 0; #pragma unroll for(int dz = 0; dz < kernel_depth; dz++){ const int z_pos = k + dz; const int k_base_z = dz * (kernel_rows * kernel_cols); #pragma unroll for(int dy = 0; dy < kernel_rows; dy++){ const int y_pos = tidy + dy; const int k_base = k_base_z + dy * kernel_cols; #pragma unroll for(int dx = 0; dx < kernel_cols; dx++){ const int x_pos = tidx + dx; v += Ms[z_pos][y_pos][x_pos] * shared_kernel[k_base + dx]; } } } output[((depth + k) * out_rows + row) * out_cols + col] = v; } else { break; } } }

Results

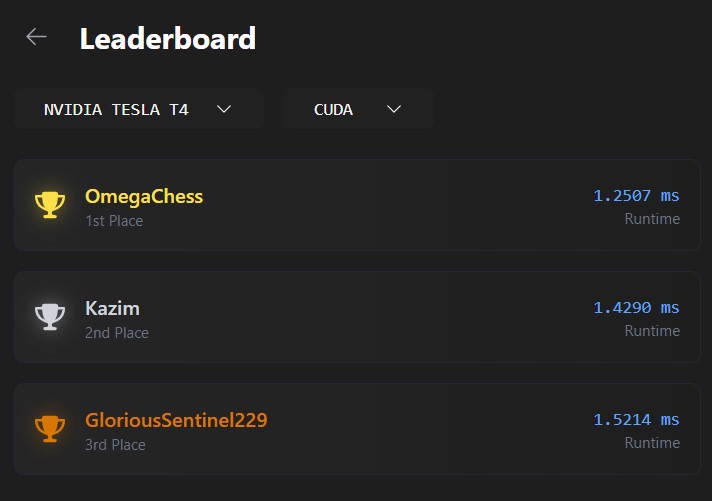

In the end, my kernel achieved the fastest time on LeetGPU's Conv3D benchmark. It reaches

1.25ms runtime, almost 4x the Naive solution!

Since it is consistently faster than the 2nd place solution by about 0.1-0.2ms, I believe

that it is likely an algorithmic advantage rather than noise.

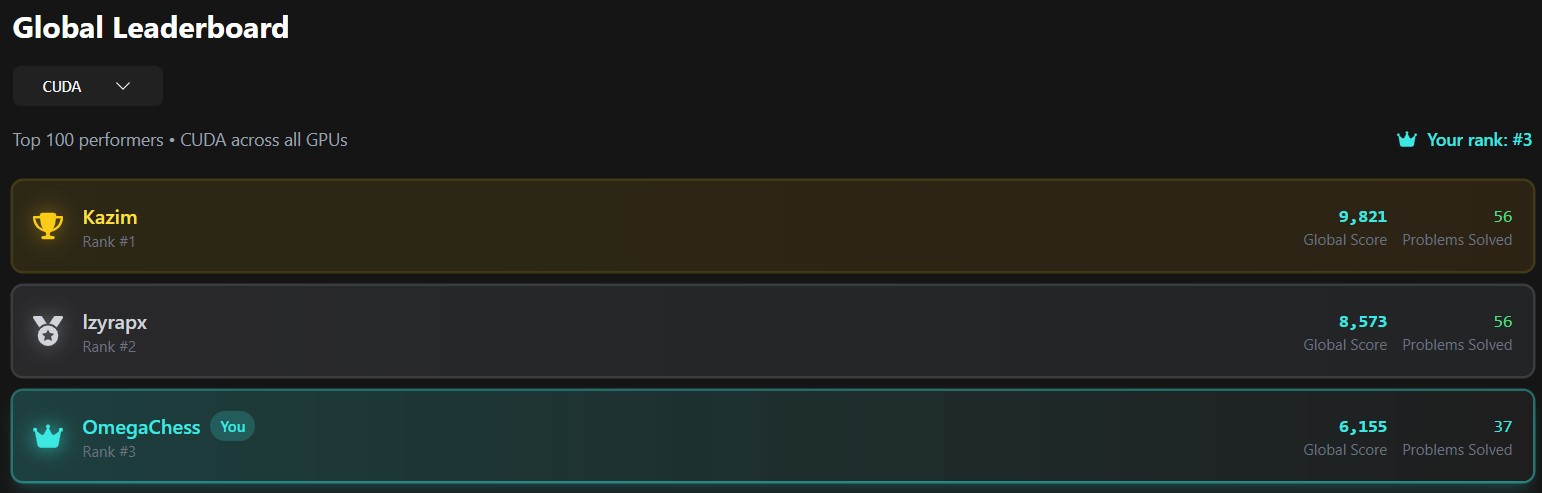

I am currently #3rd globally on LeetGPU, and have 10 fastest kernels and 13

kernels where I'm in the top 3!

More Stuff

If my cuda work was interesting, please check out my github for more:

CUDA Practice Repo

I hope you enjoyed reading the article

Any feedback is greatly appreciated! (Form is broken, message me on LinkedIn)